Management of anaemia in children living in Cameroon

Childhood anaemia represents a significant global health challenge, with the World Health Organization (WHO) estimating a global prevalence of 42% in children under five years of age. In Cameroon, around 60% of children under five are anaemic, with that percentage slightly higher in rural areas at 64.4%. The most common causes of anaemia in Cameroon are malaria, iron deficiency in diet, and intestinal parasitoses.

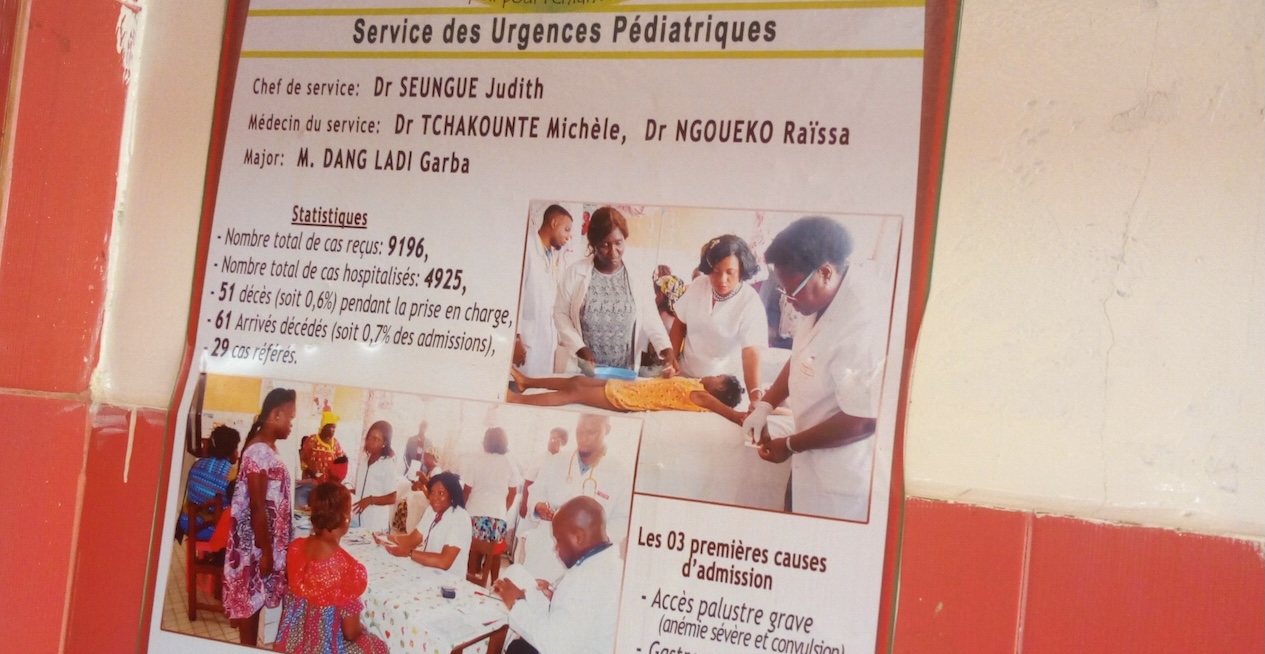

In response to the high prevalence and severe consequences of childhood anaemia, Dr Mylene Ngouéko, a medical doctor at the Mother and Child Center of Yaounde in Cameroon, planned to research the evidence and use it to help save the lives of children with severe anaemia at her hospital.

Childhood anaemia

Anaemia is defined by a lower than normal number of red blood cells or haemaglobin concentration. The most common symptoms of anaemia include fatigue, shortness of breath, dizziness and slow or delayed growth and development. Iron deficiency anaemia has also been shown to affect cognitive and physical development in children and can lead to an increased risk of child mortality.

In areas with high malaria transmission, nearly all infants and young children, as well as many older children and adults, have a reduced haemoglobin concentration as a result of malaria. Severe life-threatening malarial anaemia requiring blood transfusion in young children is a major cause of hospital admission, particularly during the rainy season when malaria transmission in highest. Young children, especially those under five years of age, are most susceptible to malaria due to a lack of acquired functional immunity, which older children and adults develop due to multiple exposures.

The plan to save children's lives

Dr Ngouéko was driven to save the lives of anaemic children at her hospital after seeing too many children die:

"I started work at the emergency department and I think I could not spend one day without losing a child because of severe anaemia … per week we could have maybe 20 children with severe anaemia".

Dr Ngouéko was sponsored by JBI's philanthropic program to participate in the JBI Evidence Implementation Training Program in Adelaide, Australia to develop the skills and knowledge required to implement evidence into practice. As part of the six-month program, Dr Ngouéko worked closely with JBI research fellows to plan, implement and evaluate an evidence implementation project to manage anaemia in children to reduce mortality at the hospital.

The first phase of the evidence implementation project aimed to determine if hospital staff treating anaemia in children complied with evidence-based guidelines for anaemia management for children aged six months to 12 years. A baseline audit revealed that evidence-based guidelines were not available for hospital staff treating anaemia in children. The audit also revealed knowledge deficits. Healthcare professionals’ knowledge of anaemia prevention and control was measured at 61%.

In addition to ensuring healthcare professionals at the hospital were equipped to manage anaemia in children at the hospital using evidence-based practice to reduce mortality, Dr Ngouéko also planned to reduce the number of admissions to the hospital of children suffering from anaemia in the first place. Therefore, families living in the community needed adequate knowledge around anaemia prevention and control, too. The baseline audit found that while 62% of families with a child receiving treatment at the hospital had adequate knowledge of anaemia, only 46% had adequate knowledge of its prevention and control.

Communicating evidence

To improve healthcare professionals’ and families’ knowledge of anaemia prevention and control, a series of strategies were put in place. These included making evidence-based guidelines available to hospital staff for the treatment of anaemia in children. Information sessions were developed and delivered to healthcare professionals to enhance their knowledge and enable them to follow evidence-based practice.

Information sessions were also delivered to families prior to the hospital discharge of their child. These families would then educate other families in their community around anaemia prevention and control. Dr Ngouéko and the evidence implementation project team found that families, wanted to know more about anaemia and anaemia prevention. They were willing learners and were enthusiastic about the project: "For the follow-up audit, they were really motivated to fill in the questionnaire", says Dr Ngouéko.

Educational posters aimed at families were displayed in the emergency department and external consultation wards. They were also strategically placed in other areas of the hospital to help educate a larger number of families - not just those with a child being treated at the hospital for anaemia.

The Getting Research into Practice (GRiP) approach was applied to identify barriers to success, and determine strategies to overcome the barriers, as well as the resources required. The project team found that the main barrier was that busy health professionals did not show the same willingness as families to engage in the project, and they were less enthusiastic about attending education sessions. To address this, the education sessions for health professionals featured Nestlé representatives as guest presenters on the subject of iron-fortified food products, and lunch was supplied.

Demonstrating impact

A follow-up audit was conducted to evaluate the impact of the implemented strategies. This audit showed that healthcare professionals’ knowledge of anaemia prevention and control strategies improved from 61% to 75%. The most significant improvement in knowledge was shown by families. Results of the follow-up audit measured families’ knowledge of anaemia at 94%, an increase from 62% in the baseline audit. Their knowledge of anaemia prevention and control strategies increased from 46% at the baseline audit to 89% in the follow-up audit.

The project’s most significant result was the families’ increased understanding of anaemia and its management, I think. The involvement of the families and their education is important in not only managing anaemia, but in preventing it in the first place. I saw the impact of education of the families.

The follow-up audit results also showed significant increases in anaemia prevention strategies undertaken by families. The rate of children aged two to 12 years receiving iron-fortified foods more than doubled from 31% in the baseline audit to 67% in the follow-up audit. The rate of malaria preventative strategies in place for children taking oral iron interventions increased from 8% to 39% in the follow-up audit.

Sustainability

The hospital has made evidence-based guidelines on the management of anaemia in children available available to staff, and education sessions for healthcare professionals continue. The hospital has also integrated the practice of educating families of children with anaemia before discharge into its routine procedures to promote sustainability.

With the success of the evidence implementation project Dr Ngouéko secured more support from food companies, senior paediatricians and general practitioners to help coordinate the outreach of iron-fortified food products. She also hopes to expand the element of the project to a larger population:

I hope to expand and continue this project so that I can reduce the mortality of children in my hospital and beyond, and maybe in Cameroon after …. Maybe we can all improve the healthcare in our country.

Continued efforts to integrate these practices into more hospitals to expand reach, could contribute to reducing the burden of childhood anaemia in Cameroon and saving the lives of children.

Take home messages

- Targeted education for families, informed by evidence, can lead to significant improvements in knowledge and adoption of preventative measures for childhood anaemia.

- Addressing the interplay between anaemia and other prevalent conditions such as malaria through integrated educational strategies is necessary is endemic settings.

Sustainability of evidence-based practices requires their integration into routine healthcare delivery and engagement of various stakeholders.

References

Ranjha, R., Singh, K., Baharia, R. K., Mohan, M., Anvikar, A. R., & Bharti, P. K. (2023). Age-specific malaria vulnerability and transmission reservoir among children. Global Pediatrics, 6, 100085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gpeds.2023.100085

White, N. J. (2018). Anaemia and malaria. Malaria Journal, 17, Article 371. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-018-2516-2

World Health Organization. (n.d.). Anaemia. https://www.who.int/health-topics/anaemia#tab=tab_1