The effect of patient education on improving self-care for transplant patients

Empowering patients to participate actively in their care is a cornerstone of high-quality, person-centred healthcare. Self-care is particularly important for transplant recipients, whose complex medical needs and lifelong self-management responsibilities demand ongoing support, accurate education, and evidence-based clinical guidance. At the National University Hospital in Singapore nurses are leading evidence-based approaches to improve health outcomes and foster patient independence.

Introduction

The National University Hospital is a tertiary hospital and major referral centre with over 50 medical, surgical and dental specialities, offering a comprehensive suite of specialist care. It is the only public hospital in Singapore to offer a paediatric kidney and liver transplant programme, in addition to kidney, liver and pancreas transplantation for adults.

As an academic health institution, patient safety and good clinical outcomes are the focus of the hospital. The National University Hospital takes great pride in translating research evidence into practice and is at the forefront of advocating evidence-based nursing to influence positive clinical outcomes in Singapore.

Liaw Yi Qi, a senior staff nurse, attended the JBI Evidence Implementation Program to strengthen her capacity to champion practice change. Through the program, she was inspired to implement interventions that could improve self-care practices among transplant patients, a group whose health outcomes are closely tied to their ability to manage aspect of the care independently, both during hospitalisation and after discharge.

Issues uncovered

Two key areas were identified for improvement in the transplant unit. First, transplant patients are required to monitor their fluid intake as part of their post-operative care, a task that continues after discharge and plays an important role in guiding their treatment. However, the recording of fluid intake during the patients’ stay in hospital was sometimes inaccurate.

Second, as transplant patients are immunocompromised, they are highly susceptible to acquiring infections, and in particular urinary tract infections. Immunosuppressive therapies, commonly used to prevent organ rejection, make these patients more susceptible to infections while also potentially masking typical signs of UTI, complicating diagnosis and treatment. UTIs in transplant patients are concerning because they can lead to complications such as graft dysfunction, sepsis, or hospital readmission. Timely and accurate diagnosis is therefore critical. However, the lack of proper and standardised education on the collection of midstream urine needed to diagnose the bacteria responsible for UTIs resulted in contaminated samples that could not accurately guide the use of antibiotics and treatment plans for the patient.

Implementing evidence-based solutions

To address these issues, Yi Qi led a six-month, evidence-based implementation project following a structured framework involving audit and feedback cycles and the GRiP (Getting Research into Practice) method, facilitated by JBI PACES software. The project focused on improving patient education and involvement in two key areas: fluid intake charting and midstream urine sample collection.

“I am a firm believer in the use of evidence-based practice to transform patient care. I believe that wastage can be reduced through the application of validated interventions. Thus, in order to address these issues, I applied the principles that I learnt during the JBI Evidence Implementation Training Program”, says Yi Qi.

Improving Fluid Intake Monitoring

The JBI evidence summary indicated that the accuracy of charting patients’ fluid intake could be improved by involving patients in their own intake charting. To facilitate this, the project team created a patient intake chart.

This chart was given to patients immediately upon admission and nurses educated patients on the importance of fluid intake charting and explained the various volumes of cups and bowls in the hospital. Once the patients were assessed as competent, they were expected to take charge of their own charting during their hospitalisation to form a habit that would continue after discharge.

This initiative resulted in patient involvement rates increasing from 3% at baseline audit to 87% at one-month post implementation audit and continued to sustain high levels of compliance (more than 80%) a further six months’ later. Accuracy of fluid intake charting has continued to be sustained from the implementation of the project in 2018 to the present day through standardised patient education and the use of the patient intake chart.

This evidence-based initiative has helped to foster independence and empowered patients through education and involvement, and represents a shift toward patient agency and self-efficacy. For transplant patients, who must manage fluid intake rigorously to maintain organ function and avoid complications, this habit-building intervention has long-term impact. It enhances continuity of care, reduces reliance on clinical staff, and supports sustained health outcomes beyond discharge.

Reducing Urine Sample Contamination

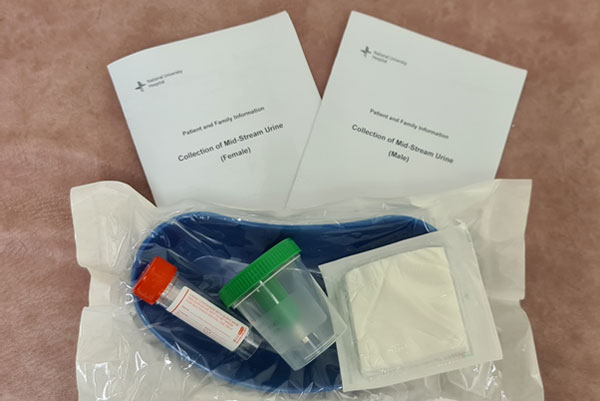

The second intervention focused on reducing urine sample contamination by educating patients on how to properly collect midstream samples. Evidence from JBI suggests that patients should be educated by a healthcare provider before collecting their own midstream urine to ensure a clean sample for urinalysis. This led to the development of a patient education leaflet which is used as a standardised guide for nurses to educate patients and for patients to keep as a reference. Visual aids in the leaflet helped patients better understand the rationale and steps involved in collecting a clean midstream urine sample. The leaflet minimises confusion and prevents conflicting instructions from nurses to patients.

A baseline audit showed that there was a 40% contamination rate of midstream urine samples. One month after the implementation of the patient education initiatives, the contamination rate of midstream urine samples decreased to 26.7%, and after three-months it dropped even further to 20%.

The use of the patient education leaflet continues to this day and has been implemented into the surgical department’s patient education program. Follow-up audits continue, and have recorded the sustained decrease in midstream urine sample contamination rates. This initiative demonstrated that optimal outcomes were more likely to be achieved by incorporating patient education into the patient’s plan of care.

Ensuring easy access to evidence

During the initial phase of the project, ward nurses highlighted the lack of availability of both the patient intake chart and the education leaflet. As these initiatives were newly implemented, only the hard copy version was available, and there was often a delay in being able to access the hard copies. In response to feedback from nurses, the project team made soft copies available on point-of-care computers, which allowed nurses to print information for patients from whichever computer terminal they were on. This not only ensured the resources were available at all times, it was also easier for the nurses to gain quick access to the resources instead of having to rely on a single access point in the ward.

Sustaining evidence-based change

The success of the project can be attributed in part to the positive attitudes of the nurses. They were extremely involved throughout the change process and were willing to adopt the new processes to help patients achieve better outcomes, even if it meant spending additional time on the new educational initiatives. Nurses took ownership of the project, and their dedication helped embed the new evidence-based practices into hospital guidelines and daily routines in the ward, supporting sustainability over the long term.

“With the continuous advancement of technology, patients and their families are no longer passive consumers in the healthcare paradigm. Patients increasingly want to play a greater role in managing their health conditions. Nurses should take this opportunity to engage in patient education and continue to innovate by seeking out new technologies to enhance the patient education process, which can lead to better outcomes and quality of care” says Yi Qi.

Conclusion

This evidence implementation project illustrates the profound impact of evidence-based nursing. Addressing challenges with structured, research-informed solutions, empowers nurses to improve patient outcomes, reduce preventable harm, and strengthen patient autonomy. Transplant patients gained the skills and confidence to manage essential aspects of their care, both in hospital and at home.

“The practice changes not only help make nursing processes more efficient; patients also become more empowered, which helps us achieve the outcomes more effectively”, says Tiffany Ng, a registered nurse working in the implementation ward.

Key takeaways

The project demonstrates that when nurses are equipped to lead with evidence, and when systems support them to innovate, the benefits to patients are measurable and meaningful.

Empowering patients through structured education and active involvement improves health outcomes and builds confidence in managing complex conditions like transplant recovery.

Low-cost, evidence-informed tools such as intake charts and education leaflets can drive lasting change when embedded in everyday practice and supported by team engagement.

References

Dew, M. A., DiMartini, A. F., De Vito Dabbs, A., Myaskovsky, L., Steel, J., Unruh, M., Switzer, G., Zomak, R., Posluszny, D. M., & Kormos, R. L. (2015). Meta-analysis of medical regimen adherence outcomes in pediatric solid organ transplantation. Transplantation, 99(12), 2561–2573.

Golebiewska, J. E., Debska-Slizien, A., Rutkowski, B., & Lichodziejewska-Niemierko, M. (2014). Urinary tract infections in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation Proceedings, 46(8), 2647–2651.

Peters MDJ. Evidence summary. Urine sampling: midstream urine specimen. JBI EBP Database. JBI@Ovid. 2017; JBI13874.

World Health Organization. (2016). Framework on integrated, people-centred health services.

World Health Organization. (2022). Global report on infection prevention and control.

Additional resources

Yi Qi Liaw, Goh ML. Improving the accuracy of fluid intake charting through patient involvement in an adult surgical ward: a best practice implementation project. JBI Evid Synth. 2018;16(8):1709-19.

Yi Qi Liaw, Goh ML. Reducing contamination of midstream urine samples through standardized collection processes: a best practice implementation project. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18(1):256-71.

JBI Manual for Evidence Implementation (for the JBI Evidence Implementation Framework, including the GRiP approach)

Author

Yi Qi LiawYi Qi Liaw1,2

1. Nursing, National University Hospital, National University Health System, Singapore

2. Singapore National University Hospital (NUH) Centre for Evidence-Based Nursing, A JBI Centre of Excellence

Disclaimer

Republished with permission from World Evidence-based Healthcare Day https://worldebhcday.org/stories/story?ebhc_impact_story_id=73