Advance care planning at the UCSF

June 2025

Philip Garcia MS, RN, PCCN1, Hannah Jang Kim PhD, RN, CNL, PHN2, Susan Barbour MS, RN, ACHPN, CNS1, Adam Cooper DNP, RN, NPD-BC, EBP-C1,2

1UCSF Centre for Evidence Implementation: a JBI Centre of Excellence

2UCSF School of Nursing

University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Health is internationally renowned for providing highly specialised and innovative care. Based in the city of San Francisco, care is provided across four different campuses and over 300 ambulatory care areas. UCSF Health is among the top hospitals in the United States and has received many recognitions, including Magnet status, which recognises nursing excellence. UCSF Health is an academic medical centre with over 1,200 beds and is part of UCSF, one of the top universities in the nation for health sciences research and higher education. By bringing together the world's leading experts in nearly every area of health, advancements in treatment and technology that benefit patients everywhere can be achieved.

Advance care planning (ACP) includes discussions and decisions about emergency response status, such as full-code or do-not-resuscitate, completing an advance care directive, identifying healthcare agents/surrogates, and decisions regarding life-sustaining treatments. To help improve the practice of ACP, Philip Garcia, an experienced nurse in the Medicine Transitional Care Unit (MTCU), led an evidence-based implementation project. In the context of Philip’s project, ‘ACP’ refers to discussions that patients have with their selected decision makers and/or healthcare providers about their goals regarding certain treatments, especially at the end of life. Unfortunately, ACP communication and documentation is often inadequate, leading to care that is inconsistent with patients’ preferences. This can result in moral dilemmas for families. Nurses are patient advocates, optimally positioned to initiate ACP, but many feel that they lack the training and skills to navigate these conversations. Since these goals and wishes are often shared with nurses, it is important for them to have the knowledge and comfort to navigate and document these conversations.

Philip’s project was carried out on his home nursing unit, the MTCU, also known as a progressive care unit. This unit primarily serves patients on the medicine service, but up to ten different provider services admit patients to the MTCU. Nurses care for patients requiring continuous telemetry and pulse-oximetry monitoring, with interventions occurring as frequently as every two hours, and administer high-risk intravenous medications. These highly skilled nurses respond quickly to the complex medical needs of patients; however, they lacked the confidence to carry out vital conversations that may mitigate urgent decision-making. Philip’s project aimed to increase nurses’ capacity to initiate and document ACP conversations to provide care congruent with patients’ goals and values.

While the primary focus of Philip’s project was the MTCU nurses, team members and stakeholders were needed to ensure success. As the project lead, Philip developed and executed the training, and conducted audits. The palliative care clinical nurse specialist was the clinical coach. A nursing professional development specialist and nurse scientist provided guidance and training on quality improvement, ensuring that the JBI framework was optimally utilised. Other sources of support included eight staff nurses from the day and night shifts who volunteered as project team members, unit leaders, a palliative care social worker, physician co-leads of a previous ACP initiative, chief medical residents, and an information technologist.

Philip’s project used the JBI audit and feedback method to implement the evidence into practice. The JBI Practical Application of Clinical Evidence System (JBI PACES) and Getting Research into Practice (GRiP) audit tools informed decision-making to incorporate ACP into the nursing workflow. Eight audit criteria were created, based on a JBI evidence summary. These were combined with input from clinical experts and instructions from the institution’s risk management, respectively, to serve as a guide for education and evaluation of ACP notes. Philip states:

‘The JBI evidence summaries were integral in developing interventions to promote uptake of a new practice; without them it would’ve been much more challenging to know where to start. I also really appreciated that they provided available evidence; this catalyzed my literature review.’

Philip reviewed ACP notes from electronic health records and online survey responses to determine compliance with best practices. Change strategies were developed in response to follow-up audits using JBI’s GRiP tool. This allowed the team to explore barriers to best practices and to develop and implement strategies to increase compliance.

Key activities and strategies that were undertaken

Implementation occurred over three months along with regular monthly evaluation of barriers and strategies to address these barriers. The team reviewed the JBI Evidence Summaries and integrated these with findings from their literature review. The collaborative nature of this process assured Philip’s team that their plan would prove effective. Taking into account the bustling nature of the MTCU, passive and efficient training methods were selected.

The team identified that the keys to facilitating increased ACP engagement included an educational presentation, just-in-time small group sessions, informative posters in the charting room, conversation prompts at computer workstations, and badge-sized reference cards to reinforce education or aid in unprompted conversations.

All printed materials were also emailed to staff and made readily available for download on a file-sharing platform. One nurse stated: ‘I find the posters around the unit very helpful on how to start conversations about ACP, examples of one-liners we could use to open up those difficult conversations…are realistic.’

The educational presentation was the launching pad of the project. It informed the nurses of their role in ACP, defined key terms, and how to introduce the topic. Nursing staff found the just-in-time sessions to be the most helpful in conceptualising the information they received, and this provided the opportunity to practice with colleagues.

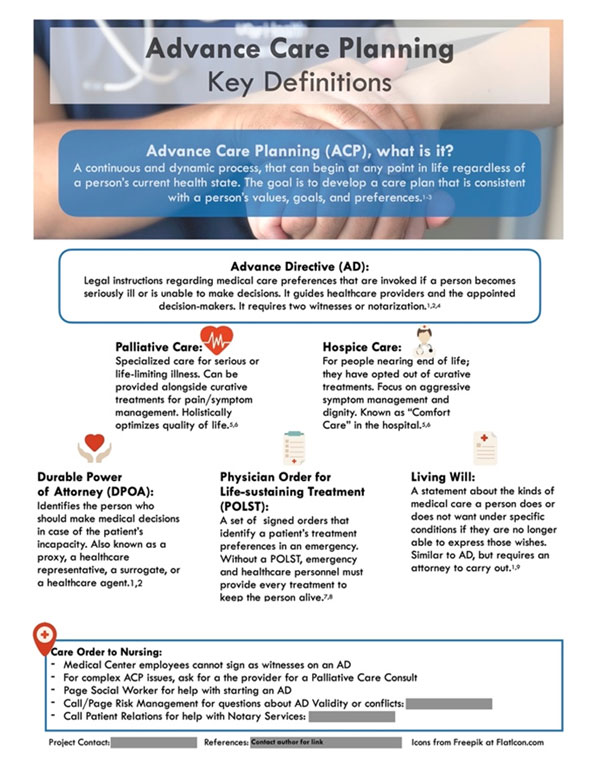

Educating nurses about ACP terms was required to empower their engagement in ACP. Guided by the literature, Philip educated the staff about defining advance directives (AD), durable power of attorney (DPOA)/surrogate decision maker, physician’s orders for life sustaining treatment (POLST), and living wills.

Three follow-up audits measured the sustainability of the initiative. Effectiveness was measured through an anonymous online survey, a handful of informal conversations with staff, and ACP notes written by MTCU nurses. The notes were evaluated for the inclusion of four best practice elements: 1) psychosocial wellbeing, 2) treatment preferences, 3) values, and 4) quality of life indicators.

Outcomes of activities

The online survey evaluated whether nurses had conversations and their understanding of terms, as well as requesting feedback on the interventions. The baseline yielded 47 survey responses with no ACP notes (0% compliance). At conclusion, there were 49 survey responses and 12 ACP notes. At baseline, 12 (26%) nurses reported being able to describe all four terms to patients, but the final audit revealed an increase to 36 (73%) nurses. Compliance with the best practice recommendation for nurses to engage in ACP discussions increased from 55% to 80%. Of the notes in the final audit, 42% included all best practice elements and 92% included patients’ treatment preferences. Many of the nurses (86%) found just-in-time training moderately or extremely useful. An average of 96% indicated a better understanding of when and how to discuss ACP at the project’s conclusion. This data was derived from JBI PACES. What these results indicate is that there was uptake of the practice into nursing workflow.

Lessons for the future: Sustainability and transferability

Rigorous JBI audit criteria strengthened the project by establishing a framework in which creative pivots were implemented. It was helpful that JBI PACES produced images and calculated the percentage of compliance, while the GRiP tool helped the team to work through the barriers and facilitators. Frequent surveying helped to examine the sustainability and applicability of educational methods. One nurse stated: ‘With the posters and resources around the unit, it has been easier to engage in these discussions. There are quick and fast prompts that we can use, and it's easy to incorporate them into our daily assessments.’

Since the conclusion of the project, the posters and printed prompts were shared with other departments. Philip has provided ACP-related training to four cohorts of new nurse-residents, and at two sessions of palliative care resource nurse training, where he distributed badge-sized reference cards. However, a broad uptake of the practice has been challenged by various factors uncovered during the project. These included time, high patient acuity and persistent nurse discomfort. From experience, Philip believes that the conversations are happening, but they are not being documented.

A limitation of this project is that it relied heavily on ACP notes to measure five audit criteria. This may not have provided a full picture of the nurses’ practices because, as one nurse stated, ‘Usually, these conversations develop on the spot when someone is expressing a specific feeling or concern.’ A second nurse stated: ‘I think most of the time we would forget to document we had a discussion about ACP; sometimes, it seems like a very casual conversation or a conversation in passing about advanced care planning that we don't realize we have to document it.’

There was also no measurement of patient outcomes such as filed ADs or POLSTs, which would require a project of its own and a culture change within the community of clinicians.

When preparing the interventions, Philip noted that most online references targeted physicians and advance practice providers. The lack of nurse-focused references contributes to a lack of confidence among nurses, and the perception that the nurse’s role in these conversations and subsequent notes does not add to the care of the patient. Seeking evidence that affirms nursing roles and acknowledges nursing practices is key.

A nurse stated: ‘I feel intimidated having these conversations because the doctors might have conflicting ideas and they might say something that sounds different from what I say to the patients. I think if there's a mutual understanding between the MD team and nurses first, it would be easier for us to have these conversations with patients.’

With targeted education, nurses are more likely to engage in ACP conversations. Future initiatives would benefit from incorporating practical opportunities without real-life implications and providing continued support to cohorts through check-in sessions. It would also be beneficial to arrange expert shadowing for nurses to witness how the conversations unfold. Future project leaders must address nurses’ hesitations regarding ACP and time constraints when implementing initiatives. Institutions must provide support and funding and develop an integrative nursing education plan to empower nurses to have and document these vital conversations because nurses are part of the conversation.

Links to additional resources

Garcia, P., Kim, H.J., Barbour, S., & Cooper, A. (2023). Empowering nurses to increase engagement in advance care planning on a medicine transitional care unit: A best practice implementation project. JBI Evidence Implementation, 21(4), 310-324. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000373.